missionary biographies & adventures

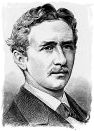

| Alexander M. Mackay (1849-1890) was a pioneer engineer-missionary to Uganda. Arrived in Zanzibar in 1876; he reached Uganda in 1878. Built 230 miles of road to Uganda from the coast. Translated Matthew's Gospel into Luganda. Died in 1890 having spent fourteen years in Africa without once returning home to native Scotland. |

The inquisitive village folk stared over their garden gates at Mr. Mackay, the minister of the Free Kirk of Rhynie, a small Aberdeenshire village, as he stood with his thirteen-year-old boy gazing into the road at their feet. The father was apparently scratching at the stones and dust with his stick. The villagers shook their heads.

"Fat's the minister glowerin' at, wi' his loon Alic, among the stoor o' the turnpike?" ("What is the minister gazing at, with his son Alec, in the dust of the road?") asked the villagers of one another.

The minister certainly was powerful in the pulpit, but his ways were more than they could understand. He was for ever hammering at the rocks on the moor and lugging ugly lumps of useless stone homeward, containing "fossils" as he called them.

Now Mr. Mackay was standing looking as though he were trying to find something that he had lost in the road. If they had been near enough to Alec and his father they would have heard words like these:

"You see, Alec, this is the Zambesi River running down from the heart of Africa into the Indian Ocean, and here running into the Zambesi from the north is a tributary, the Shiré. Livingstone going up that river found violent natives who..."

So the father was tracing in the dust of the road with the point of his stick the course of the Zambesi which Livingstone had just explored for the first time.

On these walks with his father, Alec, with his blue eyes wide open, used to listen to stories like the marvellous adventures of Livingstone. Sometimes Mr. Mackay would stop and draw triangles and circles with his stick. Then Alec would be learning a problem in Euclid on this strange "blackboard" of the road. He learned the Euclid—but he preferred the Zambesi and Livingstone.

One day Alec was off by himself trudging down the road with a fixed purpose in his mind, a purpose that seemed to have nothing in the world to do with either Africa or Euclid. He marched away from his little village of Rhynie, where the burn [a stream or brook] runs around the foot of the great granite mountain across the strath [wide river valley]. He trudged on for four miles. Then he heard a shrill whistle. Would he be late after all? He ran swiftly toward the little railway station. A ribbon of smoke showed over the cutting, away to the right. Alec entered the station and ran to one end of the platform as the train slowed down and the engine stopped just opposite where he stood.

He gazed at the driver and his mate on the footplate [the part of a railroad locomotive from which the driver operates the controls]. He followed every movement as the driver came round the engine with his long-nosed oil-can, and opened and shut small brass lids and felt the bearings with his hand to see whether they were hot. The guard waved his green flag. The whistle of the engine shrieked, and the train steamed out of the station along the burn-side [the side of the stream or brook] toward Huntly. Alec gazed down the line till the train was out of sight and then, turning, left the station and trudged homeward. When he reached Rhynie he had walked eight miles to look at a railway engine for two and a half minutes—and he was happy!

As he went along the village street he heard a familiar sound.

"Clang—a—clang clang!—ssssssss!" It was irresistible. He stopped, and stepped into the magic cavern of darkness, gleaming with the forge-fire, where George Lobban, the smith, having hammered a glowing horseshoe into shape, gripped it with his pincers and flung it hissing into the water.

Having cracked a joke with the laughing smith, Alec dragged himself away from the smithy, past the green, and looked in at the stable to curry-comb the pony and enjoy feeling the little beast's muzzle nosing in his hand for oats.

He let himself into the manse [Christian minister's house] and ran up to his work-room, where he began to print off some pages that he had set up on his little printing press.

At supper his mother looked sadly at her boy with his dancing eyes as he told her about the wonders of the railway engine. In her heart she wanted him to be a minister. And she did not see any sign that this boy would ever become one: this lad of hers who was always running off from his books to peer into the furnaces of the gas works, or to tease the village carpenter into letting him plane a board, or to sit, with chin in hands and elbows on knees, watching the saddler cutting and padding and stitching his leather, or to creep into the carding-mill [where wool would be brushed, or carded so it could be spun into yarn for knitting or used for weaving into cloth]—like the Budge and Toddy whose lives he had read—"to see weels go wound."

It was a bitter cold night in the Christmas vacation fourteen years later. (December 12, 1875). Alec Mackay, now a young engineering student, was lost to all sense of time as he read of the hairbreadth escapes and adventures told by the African explorer, Stanley, in his book, How I found Livingstone.

He read these words of Stanley's:

"For four months and four days I lived with Livingstone in the same house, or in the same boat, or in the same tent, and I never found a fault in him. ...Each day's life with him added to my admiration for him. His gentleness never forsakes him: his hopefulness never deserts him. His is the Spartan heroism, the inflexibility of the Roman, the enduring resolution of the Anglo-Saxon. The man has conquered me."

Alexander Mackay put down Stanley's book and gazed into the fire. Since the

days when he had trudged as a boy down to the station to see the

railway engine he had been a schoolboy in the Grammar School at Aberdeen,

and a student in Edinburgh, and while there had worked in the great

shipbuilding yards at Leith amid the clang and roar of the rivetters

and the engine shop. He was now studying in Berlin, drawing the designs

of great engines far more wonderful than the railway engine he had

almost worshipped as a boy.

Alexander Mackay put down Stanley's book and gazed into the fire. Since the

days when he had trudged as a boy down to the station to see the

railway engine he had been a schoolboy in the Grammar School at Aberdeen,

and a student in Edinburgh, and while there had worked in the great

shipbuilding yards at Leith amid the clang and roar of the rivetters

and the engine shop. He was now studying in Berlin, drawing the designs

of great engines far more wonderful than the railway engine he had

almost worshipped as a boy.

On the desk at Mackay's side lay his diary in which he wrote his thoughts. In that diary were the words that he himself had written:

"This day last year [May 1, 1873] Livingstone died—a Scotsman and a Christian—loving God and his neighbour, in the heart of Africa. 'Go thou and do likewise.'"

Mackay wondered. Could it ever be that he would go into the heart of Africa like Livingstone? It seemed impossible. What was the good of an engineer among the lakes and forests of Central Africa?

On the table by the side of Stanley's How I found Livingstone lay a newspaper, the Edinburgh Daily Review. Mackay glanced at it; then he snatched it up and read eagerly a letter which appeared there. It was a new call to Central Africa—the call, through Stanley, from King M'tesa of Uganda, that home of massacre and torture. These are some of the words that Stanley wrote:

"King M'tesa of Uganda has been asking me about the white man's God. ...Oh that some practical missionary would come here. M'tesa would give him anything that he desired—houses, land, cattle, ivory. It is the practical Christian who can ... cure their diseases, build dwellings, teach farming and turn his hand to anything like a sailor—this is the man who is wanted. Such a one, if he can be found, would become the saviour of Africa."

Stanley called for "a practical man who could turn his hand to anything—if he can be found."

The words burned their way into Mackay's very soul.

"If he can be found." Why here, here in this very room he sits—the boy who has worked in the village at the carpenter's bench and the saddler's table, in the smithy and the mill, when his mother wished him to be at his books; the lad who has watched the ships building in the docks of Aberdeen, and has himself with hammer and file and lathe built and made machines in the engineering works—he is here—the "man who can turn his hand to anything." And he had, we remember, already written in his diary:

"Livingstone died—a Scotsman and a Christian—loving God and his neighbour, in the heart of Africa. 'Go thou and do likewise.'"

Mackay did not hesitate. Then and there he took pen and ink and paper and wrote to London to the Church Missionary Society which was offering, in the daily paper that lay before him, to send men out to King M'tesa. The words that Mackay wrote were these:

"My heart burns for the deliverance of Africa, and if you can send me to any one of those regions which Livingstone and Stanley have found to be groaning under the curse of the slave-hunter I shall be very glad."

Within four months Mackay, with some other young missionaries who had volunteered for the same great work, was standing on the deck of the S.S. Peshawur as she steamed out from Southampton for Zanzibar.

He was in the footsteps of Livingstone—"a Scotsman and a Christian"—making for the heart of Africa and "ready to turn his hand to anything" for the sake of Him who as

"...the Carpenter of Nazareth

Made common things for God."

Alexander Mackay: The Roadmaker

After many months of delay at Zanzibar, Mackay with his companions and bearers started on his tramp of hundreds of miles along narrow footpaths, often through swamps, delayed by fierce greedy chiefs who demanded many cloths before they would let the travellers pass. One of the little band of missionaries had already died of fever. When hundreds of miles from the coast, Mackay was stricken with fever and nearly died. His companions sent him back to the coast again to recover, and they themselves went on and put together the Daisy, the boat which the bearers had carried in sections on their heads, on the shore of Victoria Nyanza. So Mackay, racked with fever, was carried back by his Africans over the weary miles through swamp and forest to the coast. At last he was well again, and with infinite labour he cut a great wagon road for 230 miles to Mpapwa. With pick and shovel, axe and saw, they cleared the road of trees for a hundred days.

Mackay wrote home as he sat at night tired by the side of his half-made road, "This will certainly yet be a highway for the King Himself; and all that pass this way will come to know His Name."

At length, after triumphing by sheer skill and will over a thousand difficulties, Mackay reached the southern shore of Victoria Nyanza at Kagei, to find that his surviving companions had gone on to Uganda in an Arab sailing-dhow [ship], leaving on the shore the Daisy, which had been too small to carry them.

On the beach by the side of that great inland sea, Victoria Nyanza, in the heart of Africa, Mackay found the now broken and leaking Daisy. Her cedar planks were twisted and had warped in the blazing sun till every seam gaped. A hippopotamus had crunched her bow between his terrible jaws. Many of her timbers had crumbled before the still greater foe of the African boat-builder—the white ant.

Now, under her shadow lay the man "who could turn his hand to anything," on his back with hammer and chisel in hand. He was riveting a plate of copper on the hull of the Daisy. Already he had nailed sheets of zinc and lead on stern and bow, and had driven cotton wool picked from the bushes by the lake into the seams to caulk some of the leaks. Around the boat stood crowds of Africans, their dark faces full of astonishment at the white man mending his big canoe.

"Why should a man toil so terribly hard?" they wondered.

The tribesmen of the lake had only canoes hollowed out from a tree-trunk, or made of some planks sewn together with fibres from the banana tree.

At last Mackay had his boat ready to sail up the Victoria Nyanza. The whole of the length of that great sea, itself larger than his own native Scotland, still separated Mackay from the land of Uganda for which he had left Britain over fifteen months earlier.

All through his disappointments and difficulties Mackay fought on. With him, as with Livingstone, nothing had power to break his spirit or quench his burning determination to carry on his God-given plan to serve Africa.

Every use of saw and hammer and chisel, every

"trick of the tool's true trade,"

all the training in the shipbuilding yards and engineering shops at Edinburgh and in Germany helped Mackay to invent some new, daring and ingenious way out of every fresh difficulty.

The Wreck of the "Daisy"

Now at last the Daisy was on the water again; and Mackay and his bearers went aboard (August 23, 1878) and hoisting sail from Kagei ran northward. Before they had gone far black storm clouds swept across the sky. Night fell. Lightning blazed unceasingly and flung up into silhouette the wild outlines of the mountains to the east. The roar of the thunder echoed above the wail of the wind and the threshing of the waves.

All through the dark, Mackay and those of his men who could handle an oar rowed unceasingly. Again and again he threw out his twenty-fathom line, but in vain. He made out a dim line of precipitous cliffs, yet the water seemed fathomless—the only map in existence was a rough one that Stanley had made. At last the lead touched bottom at fourteen fathoms. In the dim light of dawn they rowed and sailed toward a shady beach before the cliffs, and anchored in three and a half fathoms of water.

The storm passed; but the waves from the open sea came roaring in and broke over the Daisy. The bowsprit dipped under the anchor chain, and the whole bulwark on the weatherside was carried away. The next sea swept into the open and now sinking boat. By frantic efforts they heaved up the anchor and the next wave swung the Daisy with a crash onto the beach, where the waves pounded her to a complete wreck, wrenching the planks from the keel. But Mackay and his men managed to rescue her cargo before she went to pieces.

They were wrecked on a shore where Stanley, the great explorer, had years before had a hairbreadth escape from massacre at the hands of the natives. But Stanley, living up to the practice he had learned from Livingstone, had turned enemies into friends, and now the natives made no attack on the shipwrecked Mackay.

For eight weeks Mackay laboured there, hard on the edge of the lake, living on the beach in a tent made of spars and sails. With hammer and chisel and saw he worked unsparingly at his task. He cut the middle eight feet from the boat, and bringing her stern and stem together patched the broken ends with wood from the middle part. After two months' work the now dumpier Daisy took the water again, and carried Mackay and his men safely up the long shores of Victoria Nyanza to the goal of all his travelling, the capital of M'tesa, King of Uganda.

The rolling tattoo of goat-skin drums filled the royal reception-hall of King M'tesa, as the great tyrant entered with his chiefs. M'tesa, his dark, cruel heavy face in vivid contrast with his spotless white robe, sat heavily down on his stool of State, while brazen trumpets sent to him from England blared as Mackay entered. The chiefs squatted on low stools and on the rush-strewn mud-floor before the King. At his side stood his Prime Minister, the Katikiro, a smaller man than the King, but swifter and more far-sighted. The Katikiro was dressed in a snowy-white Arab gown covered by a black mantle trimmed with gold. In his hard, guilty face treacherous cunning and masterful cruelty were blended.

M'tesa was gracious to Mackay, and gave him land on which to build his home. More important to Mackay than even his hut was his workshop, where he quickly fixed his forge and anvil, vise and lathe, and grindstone, for he was now in the place where he could practise his skill. It was for this that he had left home and friends, and pressed on in spite of fever and shipwreck to serve Africa and lead her to the worship of Jesus Christ by working and teaching as our Lord did when on earth.

One day the wide thatched roof of that workshop shaded from the flaming rays of the sun a crowded circle of the chiefs of Uganda with their slaves, who loved to come to "hear the bellows roar." They were gazing at Mackay, whose strong, bare right arm was swinging his hammer

"Clang-a-clang-clang:"

Then a ruddy glow lit up the dark faces of the watchers and the bronzed face of the white man who in the center of his workshop was blowing up his forge fire. Gripping in his pincers the iron hoe that was now redhot, Mackay hammered it into shape and then plunged it all hissing into the bath of water that stood by him.

Hardly had the cloud of steam risen from the bath, when Mackay once more gripped the hoe, and moving to his grindstone placed his foot on the pedal and set the edge of the hoe against the whirling stone. The sparks flew high. A murmur came from the Uganda chiefs who stood around.

"It is witchcraft," they said to one another. "It is witchcraft by which Mazunga-wa-Kazi makes the hard iron tenfold harder in the water. It is witchcraft by which he sends the wheels round and makes our hoes sharp. Surely he is the great wizard."

Mackay caught the sound of the new name that they had given him—Mazunga-wa-Kazi—the White-Man-at-Work. They called him by this name because to them it was very strange that any man should work with his own hands.

"Women are for work," said the chiefs. "Men go to talk with the King, and to fight and eat."

Mackay paused in his work and turned [to] them.

"No," he said, "you are wrong. God made man with one stomach and with two hands in order that he may work twice as much as he eats." And Mackay held out before them his own hands blackened with the work of the smithy, rough with the handling of hammer and saw, the file and lathe. "But you," and he turned [to] them with a laugh and pointed to their sleek bodies as they shone in the glow of the forge fire, "you are all stomach and no hands."

They grinned sheepishly at one another under this attack, and, as Mackay let down the fire and put away his tools, they strolled off to the hill on which the King's beehive-shaped thatched palace was built.

Mackay climbed up the hill on the side of which his workshop stood. From the ridge he gazed over the low-lying marsh from which the women were bearing on their heads the water-pots. He knew that the men and women of the land were suffering from fearful illnesses. He now realised that the fevers came from the poisonous waters of the marsh. He made up his mind how he could help them with his skill. They must have pure water; yet they knew nothing of wells.

Mackay at once searched the hill-side with his spade and found a bed of clay emerging from the side of the hill. He climbed sixteen feet higher up the hill and, bringing the men who could help him together, began digging. He knew that he would reach spring water at the level of the clay, for the rains that had filtered through the earth would stop there.

The Baganda (the people of Uganda) thought that he was mad. "Whoever," they asked one another, "heard of digging in the top of a hill for water?"

"When the hole is so deep," said Mackay, measuring out sixteen feet, "water will come, pure and clean, and you will not need to carry it up the hill from the marsh."

They dug and dug till the hole was too deep to hurl the earth up over the edge. Then Mackay made a pulley, which seemed a magic thing to them, for they could not yet understand the working of wheels; and with rope and bucket the earth was pulled up. Exactly at the depth of sixteen feet the water welled in. The Baganda clapped their hands and danced with delight.

"Mackay is the great wizard. He is the mighty spirit," they cried. "The King must come to see this."

King M'tesa himself wondered at the story of the making of the well and the finding of the water. He gave orders that he was to be carried to view this great wonder. His eyes rolled with astonishment as he saw it and heard of the wonders that were wrought by the work of men.

Yet M'tesa and his men still wondered why any man should work hard. Mackay tried to explain this to the King when he sat in his reception-hall. Work, Mackay told M'tesa, is the noblest thing a man can do, and he told him how Jesus Christ, the Son of the Great Father Spirit who made all things, did not Himself feel that work was a thing too mean for Him. For our Lord, when He lived on earth at Nazareth, worked with His own hands at the carpenter's bench, and made all labour forever noble.

From The Book of Missionary Heroes by Basil Mathews. New York: George H. Doran, ©1922.

>> More Missionary Biographies & Adventures